- The Lab Report Dallas

- Posts

- Randy Bowman's Radical Philanthropy

Randy Bowman's Radical Philanthropy

At a time of great need, the founder of a nonprofit boarding operation believes philanthropic organizations can learn even more from the people they serve.

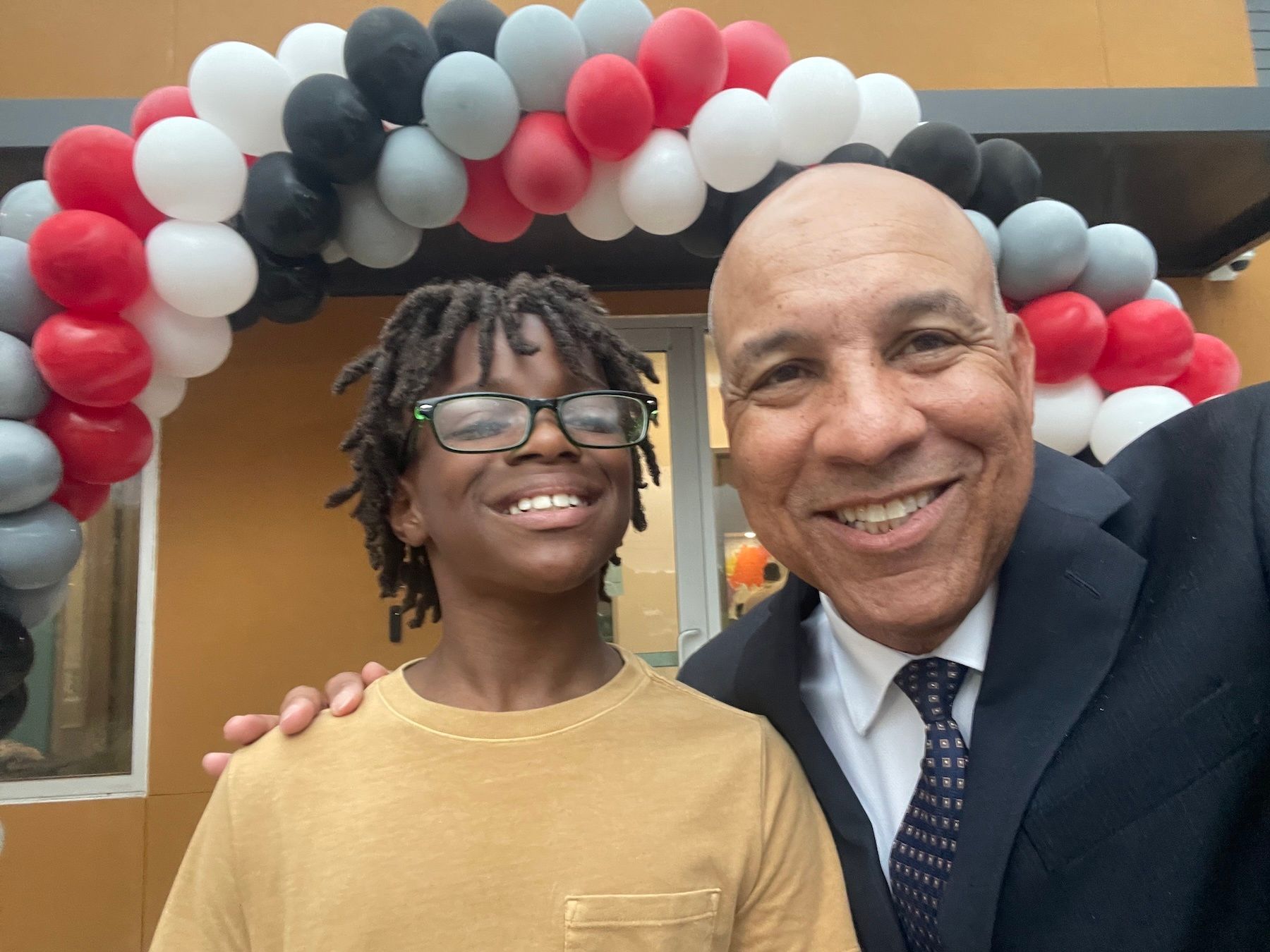

Randy Bowman, founder and CEO of AT LAST!, with Derrick Hicks, a graduate of the nonprofit’s program. (Photo courtesy Randy Bowman)

Unprecedented federal spending cuts continue to thwart the efforts of local nonprofits to mend the holes that have grown in the social-services safety net since January. Most recently, with the government’s shutdown now the longest in history, the U.S. Department of Agriculture announced that November’s federal food benefits, known as SNAP, will not be issued starting Saturday.

As philanthropists, nonprofits, and other groups face a bigger challenge than ever before, Dallas businessman and nonprofit leader Randy Bowman has some interesting ideas to share—wisdom gleaned from his firsthand knowledge of the difficulties faced by students living in poverty. Before dedicating his life to philanthropy, Bowman built an entertainment law practice and launched a logistics company that counted Fortune 500 companies among its clients.

These days, he is focused on expanding his nonprofit, called AT LAST!, an urban boarding experience in which children still attend their local schools but spend weeknights living in communal residence halls with structured support. Twelve students are currently admitted and another four will be selected in November. The nonprofit plans a second residence for another 84 children; Communities Foundation of Texas is the lead donor and the building is expected to open in late 2027.

The goal is a nontraditional approach to help these students grow academically and socially. It’s an idea born out of Bowman’s own experience growing up as a poor kid in Pleasant Grove, and his candid grasp of the struggles his mother faced as she tried, often unsuccessfully, to feed her children and get them adequate medical care. His mother, Annie Lois, died in 2021, just before At Last opened. Bowman sees her in all the moms who make the decision to entrust their children to him.

In philanthropic circles, worries often focus on donors who walk away because their dollars don’t seem to be making a difference, but Bowman knows it’s sometimes the recipients who give up. I wanted to dig deeper into his thoughts on this, as well as on the opportunities for nonprofits and the philanthropy community to do better at this critical juncture in the nation’s history. The conversation below has been edited for length and clarity.

TLR: Your life has given you the chance to experience two sides of philanthropy—first, as a recipient of charity, then as a donor. Now you are an operator within the local philanthropic community as founder and CEO of the At Last nonprofit. So let’s start with what At Last is all about.

Bowman: At Last is a program that causes impoverished elementary school-age kids to perform better during the seven hours a day that they are in school by focusing on the educational resources available to them during the 17 hours a day they are not in school. Think of it as an immersion program. We are educational resources during the home-life portion of a day, with the kids boarding with us overnight.

Each kid who’s in our program is going to get approximately 2,805 hours of additional educational resources with us each school year. That is over and above the roughly 1,300 hours they are going to get in school. That immersion is important because the 71 percent of the day that you spend at home often overwhelms the 29 percent of the day you spend at school.

At Last is proving the underlying premise that impoverished kids can learn just as effectively as those who are not impoverished if you give them the same educational resources during the fullness of their day that their more well-heeled peers enjoy.

What led you to move into nonprofit work?

It goes back to college. That’s when I began to appreciate that my life was probably going to be lived in three phases. I’d spend the first 25 years getting a good enough education to get me out of poverty. The second 25 years I’d spend trying to get the type of family experience I longed for when I was growing up. I wanted to be a good husband, I wanted to be a good father, and I wanted to create comfort for my family during that window. And I knew at 25 years old that I’d better do my best by 50 because phase three came next, and it would take up the effort to honor the sacrifices my mom made that made my adult life possible.

I knew then I was going to circle back during phase three and try and help those moms who find themselves in the condition today that my mom was in back then—and those children who are in the condition today that 9-year-old me was in back then.

That’s still what motivates me to keep it moving. It’s accepting, more or less, that you’ve had your time to focus on you and yours. Now, we’re in phase three: Put more focus on your mom’s sacrifice, focus primarily on her legacy, and focus on enabling other moms to help their children live a better life, because that’s how you honor her sacrifices.

Does the unsettling state of things in the U.S. make it more urgent to talk about how the philanthropic community could be more impactful?

This is a conversation we should always be having. And yes, the worries about threats to programs due to federal and state funding cuts are very real. But this is also important because the wealth gap is so broad today. You have so many people struggling so intensely and the delta between them and others who are doing well is so great.

At some point, the tension that constitutes that gap challenges the social compact, the one where we all say, I’ve agreed to be in community with my fellow Americans, in which we are all sacrificing, working, and pulling for each other. If the result of that collective effort is little socioeconomic mobility, where one group always seems to get more and more and others less, it will not hold. So it’s a pressing time for this discussion for all those reasons.

The community room of the At Last facility, where kids board during the week while still attending their local schools. (Courtesy Randy Bowman)

What would you tell a skeptic about the credentials you bring to a discussion of how local philanthropy can do better?

Before the question of whether my credentials merit my having a position in this conversation, let’s start here: Dallas’ philanthropic community is broad and I definitely think it’s focusing on the right types of things, the right types of problems. You can quibble whether Problem A deserves more focus and intensity than Problem B, because you’ll always be able to quibble around allocation of focus and intensity and resource. But I don’t think that you can say that Dallas has a philanthropic ecosystem that isn’t caring enough about a broad enough swath of problems.

I enter these conversations with the humility that I was raised to have and the confidence that the journey has equipped me with. I also come with a business lens because that’s where I spent the 17 years before I decided to create At Last.

But I also have a unique perspective because I have been both a consumer—that is, recipient—in this area during my first 25 years, and a donor in this area during the last 37 years. I spent a decent amount of time heavily involved in each of those positions. I do not feel under-informed in my perspectives.

A lot of the folks who are recipients of philanthropy in the manner that I was are less likely equipped to be effective narrators, so I feel the responsibility to try and be. I still see the world through the eyes of a 9-year-old impoverished child because being one makes a lasting imprint on you. I believe I am able to effectively articulate our condition and how philanthropic approaches impact us.

I’m also an operator, which means that I now get to, from a front-row perch, regularly engage and deal with both donors in this ecosystem and recipients. Those are my stakeholders and customers.

Through all those lenses and perspectives, I grapple with the often-talked-about donor fatigue and, less talked about, but just as big a problem, a dynamic that I refer to as recipient fatigue.

What do you mean by donor fatigue and recipient fatigue?

I’ve had both and can tell you recipient fatigue is every bit as real as donor fatigue. Donor fatigue involves you parting with your money, expecting that doing so is going to create a change in the social condition. You do that enough times to no effect and eventually you just don’t have the energy to do it again. Recipient fatigue is parting with your dignity and your hope, expecting that doing so is going to bring about a change in your condition. You do that enough times and it doesn’t work out, and eventually you’ve lost your dignity and hope.

People understand what donor fatigue is, but recipient fatigue is a tougher one.

It’s not the fatigue and exhaustion that people experience as they seek remedies and solutions to try and escape poverty or mitigate the effects of it. It’s not, ‘I’m tired of looking for a solution to my problems, so I’m going to just sit down and give up.’

No, it’s, ‘I finally found the solution that the city, the county, the state, the philanthropic community says is going to resolve my issue or make it better. But that promised solution has no efficacy. It’s not effective and failed to work as promised. I fought my way through the labyrinth and the solution offered seems to be most effective in fashioning itself like a python that’s squeezed out my last measure of hope. I don’t have a great place to go to where I can recover the dignity and hope that I had invested into this solution, I don’t have a place to go back and recover what I thought would be a better life forward for my children.’

Recipient fatigue is the kind of thing that can challenge your mental health, not simply exacerbate your lack of resources. That’s a feeling my mom was familiar with, and I’m familiar with from my childhood. I know how quickly you go from being a nine year old who wonders aloud, ‘how am I supposed to make something out of these surroundings’ to being an 18 year old who realizes that you likely won’t.

How quickly you come to realize that impoverished isn’t simply something that your mom was while she was raising you. It’s something that you are now as a newly minted adult.

“We’re not where you assume our need for help begins. We’re farther back than that, no matter whose fault it is.”

What’s the recipient’s responsibility in that scenario?

That’s a fair question. Let’s have that inquiry. But if you have a problem that has been with society for a really, really long time, and it has left the vast majority of the people in the condition in which it found them, I don’t believe that none of those people were capable of making the solution work.

So often we design a solution that assumes the folks who need access to it are able to reach up and grab hold of the third rung on the ladder to get started. We’re having to stretch to try to get our fingertips over the first rung, much less the third. We’re not where you assume our need for help begins. We’re farther back than that, no matter whose fault it is. I think that’s as big of a contributor to recipient fatigue as another big one—poorly designed solutions that don’t work.

So let’s talk about those solutions that don’t work. What’s going on there?

Solution design is as big a part of failure in the nonprofit world as it is in the for-profit world, but the for-profit world seems to have a greater appreciation for it. The most effective authors of the solution to a problem are the folks who have been the sufferers of that problem. But there’s a disconnect there when the problem is being suffered by people who have been under-educated.

The comparison I’d draw is to a person who can compose great music and play it brilliantly, but that person’s never learned how to use musical notation on a staff. The composition is your solution; think of the orchestra as being the policymakers. Because you can’t place musical notation on a staff, the orchestra policy makers don’t know how to play your composition. It’s not because the person isn’t bright enough to come up with a solution, right? It’s because they don’t know how to communicate it, how to package it, and how to musically notate it on the staff of life.

It’s also a reflection of our inability to ingest and decipher what the sufferers of the problem are telling us. It’s not simply their deficit, it’s ours. If we understand them more and are more proximal to them and their lives, we might be able to understand the problem the way they’re communicating it. The deficiency is not completely unidirectional.

I feel like I need to be involved in trying to offer some of these solutions, because I’ve lived a life that not only gives me firsthand knowledge of the problem but the good fortune of an education that equips me to be able to author and communicate some of these solutions. If I can do this to try and help the condition of impoverished people in Dallas, I really want to do that, because I think it helps Dallas as a whole. And at the same time, if I authored a solution, tried it, and it didn’t work, I would close it down and admit its lack of efficacy because I do not want to be the next person who contributes one iota to recipient fatigue.

Where are the opportunities to do better?

Let’s appreciate the need to accelerate the progress and to recognize the stakes by converting every philanthropic failure into the image of somebody you love rather than a nameless, faceless stranger on whom it’s easy to ascribe fault and blame. Let’s make sure we understand who the objects of our philanthropy are and that we are designing solutions that will be effective for them, and avoid creating more recipient and donor fatigue. Let’s remember the place of humility in this process.

It would also be helpful to recognize that we don’t actually know what it costs to solve a problem that we’ve never solved. All we know is what it has cost to not effectively solve it. Keeping the cost as low as possible is not always consistent with solving the problems in the most efficient and effective way. Then we lament that we’ve spent so much money on this solution, and we’re still facing an intractable problem. I don’t think that starting by being handcuffed by the cost of failure is the best way to figure out what the cost of success might look like.

Sharon Grigsby is the co-founder and senior staff writer of The Lab Report. [email protected].

Read More From The Lab Report:

Has Oak Cliff’s Deck Park Won the Trust of Its Neighbors? Halperin Park will open in the spring over Interstate 35E, near the Dallas Zoo. Residents are watching closely.

The Perception and Truth About Violence in Dallas Despite numerous high-profile murders and violent crimes, the city is on pace for its largest decrease in homicides since well before the pandemic.

DART’s Big Problem and the Little Group that Wants to Solve It The Dallas Area Transit Alliance launched right as some of the public transportation agency’s suburban partners began pushing to defund it.

Deep Medicaid Cuts Come for Parkland The steepest reduction in the program’s history has the leaders of the county’s safety net system preparing for the unknown. Here is where things stand.

The Reality Hiding Behind Motel Room Doors Anastasia Nixon shows up to work each day to help a growing number of North Texas families who have no place else to go.

We’ll send a new story to your inbox every Wednesday. Have a friend who would appreciate it? We’d love for you to forward this email to them.

The Lab Report Dallas is a local journalism project published by the Child Poverty Action Lab (CPAL). Its newsroom operates with editorial independence.

© 2025 Child Poverty Action Lab. All rights reserved.