- The Lab Report Dallas

- Posts

- The Housing Crisis Simmering in Lake Highlands

The Housing Crisis Simmering in Lake Highlands

The Dallas tax rolls this month received an enormous bump, which may spell trouble for 20 aging apartment complexes around Interstate 635.

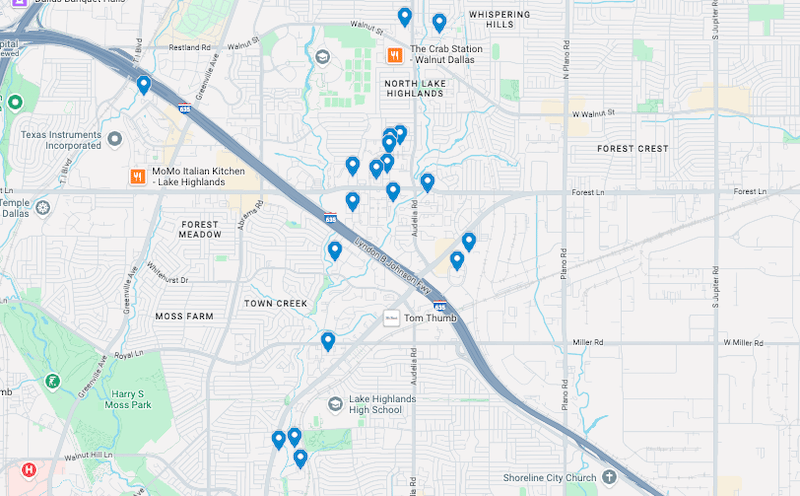

Lake Highlands is dense with aging apartment complexes, and a recent decision by the appraisal district may make it difficult for the owners to pay their debt. (Photo by Bret Redman)

The Dallas Central Appraisal District made a decision earlier this month that sent a lot of people scrambling. It quietly added nearly $3 billion worth of value back to the county’s tax rolls by denying 120 requests for tax exemptions.

This is a wonky matter with significant financial implications. The problem started with a loophole in state law that allowed obscure public housing entities to forgo paying taxes on apartment buildings they acquire in other cities, sometimes hundreds of miles away, so long as they priced some units at rates affordable to lower-income tenants. The cities losing the taxes had no say in these decisions; oftentimes, they didn’t even know the deals were happening. The properties were removed from the rolls with no public discussion as to whether the affordable units provided were worth such significant tax breaks.

This practice began in 2021 and has picked up considerably in recent years. In May, the Texas Legislature passed a bill making this illegal and Dallas’ chief appraiser proceeded to blast away the exemptions. The appraisal district’s review board upheld the decision during a hearing early in December.

DCAD clawed back an impressive amount of money; it equals a little under 2 percent of the county’s total taxable commercial value, and about three-quarters—$2.2 billion—of this haul is in the city of Dallas, in every Council district, spread across 75 complexes. (The other properties are in Carrollton, DeSoto, Duncanville, Farmers Branch, Garland, Grand Prairie, Irving, Mesquite, and Rowlett.)

In Dallas proper, their tax bills will total about $50 million annually after the appraiser’s decision, according to an analysis by the board of the Dallas Housing Finance Corporation. This should be great news for city coffers. More money for police and fire and schools and Parkland Hospital and Dallas College, just after City Hall navigated a nearly $37 million shortfall in its last budget.

But there will be unintended consequences. State lawmakers also left a mess for local officials like Council member Kathy Stewart, whose Lake Highlands district has far more of these properties than any of her colleagues. She worries that a wave of foreclosures and defaults could destabilize one of the city’s densest geographies, where aging apartments may sink into disrepair and quality of life concerns begin to spread as they did following the 2008 recession.

“My fear is, if the property goes back to the lender, lenders are not in the business of property management and working with families and tackling public safety issues,” she said in a recent interview. “In the past when I’ve watched this happen, it treads water at best, and at worst it has significant public safety issues and quality of life issues within the complex.”

How did we get here? A “housing finance corporation,” or HFC, is a tool intended to help local governments preserve affordable housing. Under the Texas Government Code, private developers can partner with these public corporations on multifamily projects to receive full tax exemptions in return for providing rental units affordable to tenants who make less than the area’s median income.

Lake Highlands has 20 “traveling HFCs,” more than any other neighborhood in the city of Dallas. (Google Maps)

HFCs most commonly acquire existing buildings and transition some portion of the units into affordable rates, which allows them to maintain a full tax exemption. This can be a powerful tool, particularly for adding affordability to more affluent neighborhoods where these deals would not otherwise pencil. However, most of the complexes DCAD has ordered to pay their tax bills were built in the 1970s or 1980s, and many are already renting for below the market rate.

Until recently, state code allowed these corporations to operate without borders. Six interlopers have been active in Dallas County, the closest of which is located 308 miles south in the town of Pleasanton, population 10,854. In lieu of taxes, the developers pay smaller amounts of annual fees to their HFC partners, resulting in millions of dollars in revenue for these other cities and counties. The counties where the apartments are actually located, however, lose tax dollars and have no say in the decision.

House Bill 21, the state law that in May banned these so-called “traveling housing finance corporations,” has emboldened some officials atop taxing entities—including Shane Docherty, DCAD’s chief appraiser—to deny the exemptions.

The “travelers,” as the appraisal district’s lawyer called them, really hit the gas as the legislation was being discussed earlier this year in Austin. Fifty-four of the 63 deals identified by Dallas’ HFC board closed within three months of the bill’s passage, which signals an aggressive attempt to receive the exemptions before lawmakers outlawed the practice.

“Why do they need to provide affordable housing miles and miles away from their local jurisdiction?” asked Peter Smith, DCAD’s legal counsel, during this month’s hearing. “That should be up to Dallas County and the cities in Dallas County to decide when, how, and where to provide affordable housing.”

“In the past when I’ve watched this happen, it treads water at best, and at worst it has significant public safety issues and quality of life issues within the complex.”

Generally, state laws are not applied retroactively. But HB 21, authored by state Rep. Gary Gates, R-Richmond, contends that this should never have been allowed, so the legislation wipes away all exemptions that do not receive local approval by Jan. 1, 2027. DCAD and appraisal districts in Travis and Bexar counties didn’t wait for that deadline. The traveling HFCs now must appeal in the courts; a lawsuit over an exemption in San Antonio is pending. Docherty said he expects the Texas Supreme Court will be the ultimate decider. (Complicating matters, the Tarrant and Harris appraisal districts granted the exemptions, paving the way for the courts to sort this out.)

“This is a case of greedy developers using the HFCs to secure property tax exemptions and other incentives in the guise of providing affordable housing,” said Smith.

In Lake Highlands, Council member Stewart is watching this situation with great concern. Twenty of the apartment buildings that had their exemptions denied are located within about a 2-mile radius, bisected by Interstate 635 along the Audelia Road corridor. That’s about three times as many as the district with the second-highest number of deals; District 6, which includes West Dallas, had seven.

The ‘Travelers’

A “traveling housing finance corporation” is an entity that partners with a developer to acquire an apartment property outside of their own jurisdiction without the knowledge of the city in which that complex is located. These apartments are then removed from the tax rolls without the other city’s knowledge. These are the six entities that have acquired properties in Dallas County.

The Cameron County Housing Finance Corporation, located 517 miles south, has six properties in the city of Dallas.

The Edcouch Community HFC, located 506 miles south, has two properties in the city of Dallas.

The La Villa HFC, located 502 miles south, has 14 properties in the city of Dallas.

The Maverick County HFC, located 409 miles southwest, has four properties in the city of Dallas.

The Pecos HFC, located 425 miles west, has 31 properties in the city of Dallas.

The Pleasanton HFC, located 318 miles south, has four properties in the city of Dallas.

The owners of the Lake Highlands properties will owe more than $13 million in taxes on their aging apartment buildings, tax records show. Some of these properties already are contending with vacancy rates higher than that of the city’s, deferred maintenance bills, and loans they are struggling to pay, according to data collected by the commercial real estate analysis firm Yardi.

David Ellis, Stewart’s appointee to the Dallas Housing Finance Corporation board, flagged the issue to the council member and began assembling a spreadsheet of the projects in District 10.

Stewart was ready to discuss the issue in October. She alerted her colleagues during a committee meeting that she had discovered what she called a housing crisis. About 7,000 apartment units that rent to low- and moderate-income residents in her district were suddenly “teetering on the edge of foreclosure,” she said then. “The financial stability of these apartment complexes is upside down. They're not performing well.”

Attorney Dan Lecavalier, who represented the six traveling HFCs in their appeal, acknowledged this possibility as he argued to the appraisal board that they should be granted at least one year of exemptions. House Bill 21 included, he said, “limited grandfathering and a transition provision so that you just don’t cause a widespread mass of defaults among individuals who have closed deals before the law changed.”

District 10 Council member Kathy Stewart is attempting to get ahead of the problem. (Photo by Sebastian Gonzalez)

Which is part of why Stewart is concerned that these deals won’t work without the tax exemption. The added tax burden might result in the borrower defaulting on the loan and the property returning to the bank. “A lender, they’re not going to pour a lot of money into it, right?” Stewart said in a recent interview at City Hall. “They’re just going to pay for the things they have to have, the utilities, whatever the basics are.”

Stewart knows these properties well. The sprawling “Bs”—The Bernard, The Beckham, The Bentley, The Baxter, The Blake—that occupy blocks of Forest Lane and Audelia Road, just north of 635, amid the smoke shops, auto garages, and old shopping centers. The “Es”—The Everly and The Emerson—that account for about 1,000 units within a circular drive just east of Skillman.

Stewart is the former executive director of the Lake Highlands Public Improvement District. Businesses pay an assessment to the PID, which uses the money for extra police patrols, beautification initiatives, infrastructure improvements, and other additions within the PID’s boundaries. A major part of Stewart's job involved working with the management companies of those apartments. What happens to those relationships if a bank takes control or puts the complex up for auction in a foreclosure?

“There’s all kinds of horror stories I could tell you; a property manager will just approve somebody because they’ll hand them $500 that they put in the bottom drawer of their desk,” she says. “What I realized is that most of the crime in our district and the PID district was happening on the properties of the multi-family [apartments], and primarily the victims of the crime were the people who lived there, these families who had come because the rents were lower and the schools were good.”

Lake Highlands, immediately south of Richardson, is perhaps best known for its schools—which are part of Richardson ISD, not Dallas—as well as its parks, trails, and the ranch-style single-family homes on wide lots. But Lake Highlands is also quite dense. The city’s planning department says much of the neighborhood was rezoned to multifamily in 1971, and the area boomed with garden-style apartments—intended for singles, now filled with couples and families—late that decade through the early 1980s.

Stewart is concerned that the properties, if returned to the lender or put up for a foreclosure auction, will fall into disrepair. (Photo by Bret Redman)

Decades-old apartment buildings now extend for miles along Audelia Road and Forest Lane. According to a 2021 city analysis, Stewart represents a part of town that has more rental units considered affordable—80 percent of the area median income, so no more than $65,760 for a single earner or $93,840 for a family of four—than any other council district: There were about 24,000 back when the analysis was performed, and half of those are considered affordable to people making even less than the 80 percent AMI threshold.

“That attracts families who need that lower rent but also want to invest in their kids and give them a good education,” Stewart says. “To me, that’s an asset.”

Vicky Taylor, the PID’s current executive director, calls the neighborhood “a small town in the city,” one where the schools bring together the kids and parents who live in apartments and those who live in single-family homes. The PID has just about doubled its assessment revenue from 2021 to 2025 in part because of increasing property values, and its 5-year service plan shows it doubling again by 2029, to about $3 million. That can help fund things like wider medians, landscaping, bonus police patrols, new signage, and community events.

“We’re an additional resource that can work on behalf of the owners in a geographic area, but what we do affects the rest of the community,” Taylor says. “Everyone comes to these events because you never know what type of services you get. We try to reach out to as many different resources as possible—nonprofits, city departments—just to bring a variety of things to be able to help our families.”

There are many examples of how these relationships have been additive for Lake Highlands. Take the nonprofit Feed Lake Highlands, an offshoot of Lake Highlands United Methodist Church that became its own entity after seeing the need in the community. The core service is a weekly food drive out of a storefront near Skillman and Audelia. About 1 in 5 children in the 75243 ZIP code—where 15 of the 20 concerning apartment properties are located—experience food insecurity. Cynthia Hernández-González, the executive director, says most of the clients are apartment residents.

“Working families,” she says. “They don’t make enough to make ends meet and they need that extra help. Either I pay my rent, or I pay my light bill, or I buy food.”

She says the organization’s goal for the next year is to do more outreach inside these complexes, to fill its “Bookmobile” van with bags of food and books and throw open its doors where people live. Doing so requires permission from property management. “If we lose that connection,” she says, “how are we going to be able to meet that need?”

Stewart’s conundrum is how to provide stability if these properties default. So she’s connecting with potential buyers who work in affordable housing.

“I’m trying to get developers interested so that they’re standing there, ready to go, when the lender takes the property back,” she says. She’s lining up a menu of funding options that could pay for infrastructure improvements or help the sales work through gap financing. “We’re just exploring our different options to make that deal close,” Stewart says.

She won’t name the developers; some are local, some are not, and at least one has indicated being interested “in a long-term hold,” which would be “phenomenal.” Stewart is attempting to get ahead of a problem and prepare for the worst possible outcome.

But there is a deadline. Without intervention from a court, their tax bills must be paid by the last day of January.

Matt Goodman is the co-founder and editor of The Lab Report. [email protected].

Read More From The Lab Report:

When Mom Can’t Come Home Last year, a program that attracted national attention for reuniting incarcerated mothers with their kids faced closure. Angelica Zaragoza helped it expand instead.

The Stubborn Story of a Challenged Apartment Complex Volara in Oak Cliff, once the most violent apartments in Dallas, last year became a tale of success. In 2025, police say it has returned to its old ways. What happened?

Oak Cliff’s Steady Heartbeat Toni Johnson is too busy at Roosevelt High School to recognize that she has become one of the most essential pieces in Dallas ISD.

A New Approach for the Most Notorious Trail in Dallas The Cottonwood Creek Trail in North Dallas has long been an unsolvable problem. City Hall’s new partners believe they know what’s been missing.

Why Starbucks is Coming to South Dallas The announcement itself is big news. But so is the story behind the decision to invite the national chain to the Forest Theater.

We’ll send a new story to your inbox every Wednesday. Have a friend who would appreciate it? We’d love for you to forward this email to them.

The Lab Report Dallas is a local journalism project published by the Child Poverty Action Lab (CPAL). Its newsroom operates with editorial independence.

© 2025 Child Poverty Action Lab. All rights reserved.