The 480-unit Volara has long been one of the locations where violence is most common in Dallas. Turning that around, police say, requires more than law enforcement. (Photo by Jason Janik)

Untruan “Train” Grant and Javier Perez spotted the boy with the long gun during their usual stroll last fall at the Volara Apartments in east Oak Cliff. The teenager was walking in the parking lot alongside a friend, who Grant and Perez knew had recently been shot. It was a weekday, and they should have been in school.

“What’s going on?” Perez asked, looking each boy in the eye. There was a shoot-out in the complex earlier in the week; teens had started walking the property with guns. “How can we support you? What’s going to help you get out of these streets?”

His brazen approach wasn’t unusual. Grant and Perez are “violence interrupters,” two formerly incarcerated men who try to de-escalate conflict and provide resources and mentorship to families in need. They knew these kids and the other children who lived at 3550 East Overton Road, a sprawling 480-unit apartment complex tucked into a heart-shaped pocket between East Illinois Avenue and Interstate 45 in southern Dallas.

The cops know this place well, too. For more than three decades, the apartments have been one of the most violent locations in the city, frequently topping what the police department calls its list of “hot spots.” News stories over the years tracked how the complex was once considered top of the line housing before being overrun by drugs, gangs, and violence, beginning in the 1980s.

The city of Dallas is poised to end 2025 with a fifth consecutive annual decline in violent crime. Police officials say they have done so by focusing their attention on specific geographies, like this one, that account for a disproportionate amount of violence. A strategy the department refers to as “place-network investigations” targets problem apartment complexes by pairing greater enforcement with quality of life and infrastructure improvements.

But violent crime doesn’t just vanish once officers drive away and buildings get fixed up. Complexes like Volara require constant vigilance and attention from entities beyond the police department. Despite declines in crime and calls for service in 2024, the property returned to the police hot spot list earlier this year.

This volatility, now sustained over decades, illustrates the difficulty in turning around the pockets of the city where violence is most common. “There are entrenched areas for generations, so two years sometimes may not be enough,” says Dallas police Lt. Matthew Allie, who oversees the teams focused on Volara and other hot spot locations.

Former Dallas police Chief David Brown lived here as a teen, when the complex was named Village Oaks. He says it was a nurturing community in the 1970s. His mother was a property manager. He remembers daily games of pick-up basketball. But when crack cocaine reached the complex in the 1980s, violence and devastation weren’t far behind. Brown says new owners took over and didn’t seem to care about the quality of the apartments or the safety of its residents. “ I hated coming back home from school,” he says.

Javier Perez, left, and Untruan “Train” Grant are trained “violence interrupters” who continued to volunteer at the complex even after their organization’s funding ran out. (Photo by Jason Janik)

The families he’d grown up with moved out, and Brown dropped out of college and became a cop so he could afford to move his own family away. Conditions worsened over the following decades, despite efforts by faith-based organizations and Brown’s own attempts to boost enforcement and community policing there when he was the city’s top cop.

“Law enforcement is not built to address trauma; they’re built to address crime,” says Grant, the violence interrupter. “You have to have other organizations that are built to address the problems and the issues that are going on in these places to help these people recover or recoup.”

Grant and Perez worked together at Dallas CRED, a violence interrupter program that was part of the city’s broader strategy to curb violent crime. It ran out of money in February—Perez now works in security while Grant is a mental health and substance abuse recovery coach—but the two still volunteer in the community.

Grant grew up in Bonton, not far from the complex, and sold drugs at Village Oaks when he was a young adult. Perez is from Michigan, where he served a 27-year sentence for murder. After his release, he moved to Dallas to be closer to his mother and help others avoid the mistakes he had made. Volara was Perez’s first assignment. It didn’t take long for residents to shed any initial distrust, particularly after meeting his dog Tarzan, a pocket bully with a mean face and a gentle spirit that enjoyed playing fetch with the kids.

In May 2022, tensions came to a head. Families of students at the complex called Maxie Johnson, then a Dallas ISD trustee, to tell him they were living without hot water, air conditioning, and gas. Horrified, Johnson reached out to local media and live-streamed the situation on Facebook. “The conditions were deplorable,” Johnson says.

Mark and Lauren Melton of the Dallas Eviction Advocacy Center saw his video and immediately drove to the property. The Meltons learned the apartments had just been bought by owners from New Jersey, who hired new managers and introduced a system to pay rent that was unfamiliar to tenants.

Court dockets showed the management company had filed evictions against 87 tenants at once. The Meltons helped about 60 people catch up on their rent or move. They worked with elderly tenants, single mothers, and families. They remember seeing kids toss around a half-filled water bottle because they didn’t have a ball. They met single mothers who spent all their money on fast food because they couldn’t cook without gas. They helped a man who had a hole in the wall of his unit so big the Meltons could see their truck in the parking lot.

“There are entrenched areas for generations, so two years sometimes may not be enough.”

Conversations about gun violence and safety were frequent, Mark Melton says, but residents seemed to accept their reality. As an affordable option for low-income families, Volara provided a home. “More than half the people there are just trying to make it work,” he says, “and they just get no mercy because of a few bad apples.”

Police, meanwhile, were in the beginning stages of a new approach that paired wraparound services with enforcement at apartments with the city’s highest crime rates. Mike Smith, a University of Texas at San Antonio criminologist who helped develop a plan for Volara, says more violence had occurred at the roughly 30-acre complex over the preceding three years than any other location in Dallas. Patrol cops began spending more time here, but crime didn’t subside. Longer-term investigations resulted in at least 20 arrests: 15 on drug and gun offenses, which were investigated with federal authorities; three believed to be connected to a shooting at the complex; and two alleged gang members who had warrants, according to a 2024 UTSA report.

The city attorney’s office sued the property owners in September 2022 for chronic nuisances. The filing noted “homes riddled with holes” as well as “peeling paint, rotted wood, inoperable toilets and appliances, rodent and insect infestations.” The city opened an office in a vacant unit at Volara for about six months. Neighborhood patrol officers worked with property management to host job fairs and recreational activities.

“It takes a village,” Smith says. “You could fix streetlights and do a lot of physical improvements even, but if you still got a violent drug gang that’s operating out of your apartment complex, then at the end of the day, that’s not really gonna matter.”

It seemed to work. The city reached a settlement agreement with property owners in 2024. By that fall, Volara entered into “maintenance mode,” which essentially meant that while police monitored the property, it was on its way to falling off the list of problem locations. A report from the UTSA criminologists cited “the level of engagement and cooperation” by the apartment managers in helping reduce violence.

But in April 2025, less than a year later, the complex landed back on the list. Allie, the Dallas lieutenant, says the reason why is complicated.

He tries to gauge whether crimes are “one-offs” or part of a larger issue. The task force that targets apartments, made up of about 40 officers, tries to fix “the problem, not always the location,” he says. For instance, drug sales at an apartment complex could be connected to a motel two miles down the road. Volara is the largest complex where police have focused, and is one of five apartments at which they’re actively working, Allie says. (Property representatives, including the owner’s attorney and top management, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

Smith, the criminologist, notes that Volara is hardly alone. “How you spread your very thin resources across a whole plethora of these kinds of complexes is—I don’t know.” There are not enough neighborhood patrol officers, he says, not enough resources. “There was a lot of effort that was devoted to Volara and it paid off,” he says. “But without a whole lot of investment, which is private and public, probably, in these kinds of places, it’s really hard to sustain that over time.”

Residents at 3550 E. Overton have noticed improvements. On recent November days, the gates were open and the grass was trimmed. Tenants live behind turquoise doors scattered across blue, slate gray, and white two-story buildings. Cameras jutted from rooftops; police placed a surveillance tower on a nearby road. Wiring hung from the top of some buildings. A broken window in one unit was boarded up. Cigarette butts occasionally littered the grass, but generally, the pathways were clear. Two golden dogs lounged under a staircase. A breeze swept orange leaves across winding roads between the complex’s buildings. Few people dawdled outside.

Police placed a surveillance tower on a nearby street, one of the many ways officers try to keep tabs on the complex when cruisers aren’t nearby. (Photo by Jason Janik)

Irma Williams has lived here for nearly 15 years with her now 99-year-old father. She recalls shootings, killings, fights, and a fire in 2014 that killed a 2-year-old girl. “It was rough,” Williams says, “but it’s way better now; you can come outside and everything.” She watches passersby outside her building. “I’ve been here too long,” the 65-year-old says, “but I just have to have a place to stay, a place to stay. Everywhere you go, the rent is high, you know, so I said I might as well stay here—been here this long, so.”

Soon after Charles Muldrow moved to the complex about four years ago, bullets shattered his window. He didn’t bother to call 911; he didn’t know who fired the gun or where the shots came from, and nobody was hurt. Now 89, Muldrow recalls the rash of evictions in the years after he first moved in. He calls the community peaceful now. “I don’t go bother nobody and nobody comes bother me,” he says.

On a different morning, Rosa Gonzalez, 63, and Jessica Barco, 37, jostled under a tree with their Chihuahua and pug puppies—Pockets, Venus, and Buttercup. They’ve been here about six months; Gonzalez previously lived nearby. She remembers it being dangerous, she says. “ Back then, drug dealers,” she says, “drug addicts. They didn’t care. But now I don’t see that happening.” She and Barco want more activities for the kids in the complex, maybe a playground, library, or gazebo. “ I see a lot of kids around here and they just run around,” Gonzalez says, pointing to a patch of grass. “It’ll keep them off the street and out of trouble.”

The violence interrupters are not surprised that the crime data and resident sentiments don’t line up. “They’re gonna always feel safer because it’s home,” Grant says, “they’re accustomed to it.” Over about three years, Perez heard requests for jobs, opportunities, resources. People didn’t know where to look and needed counseling.

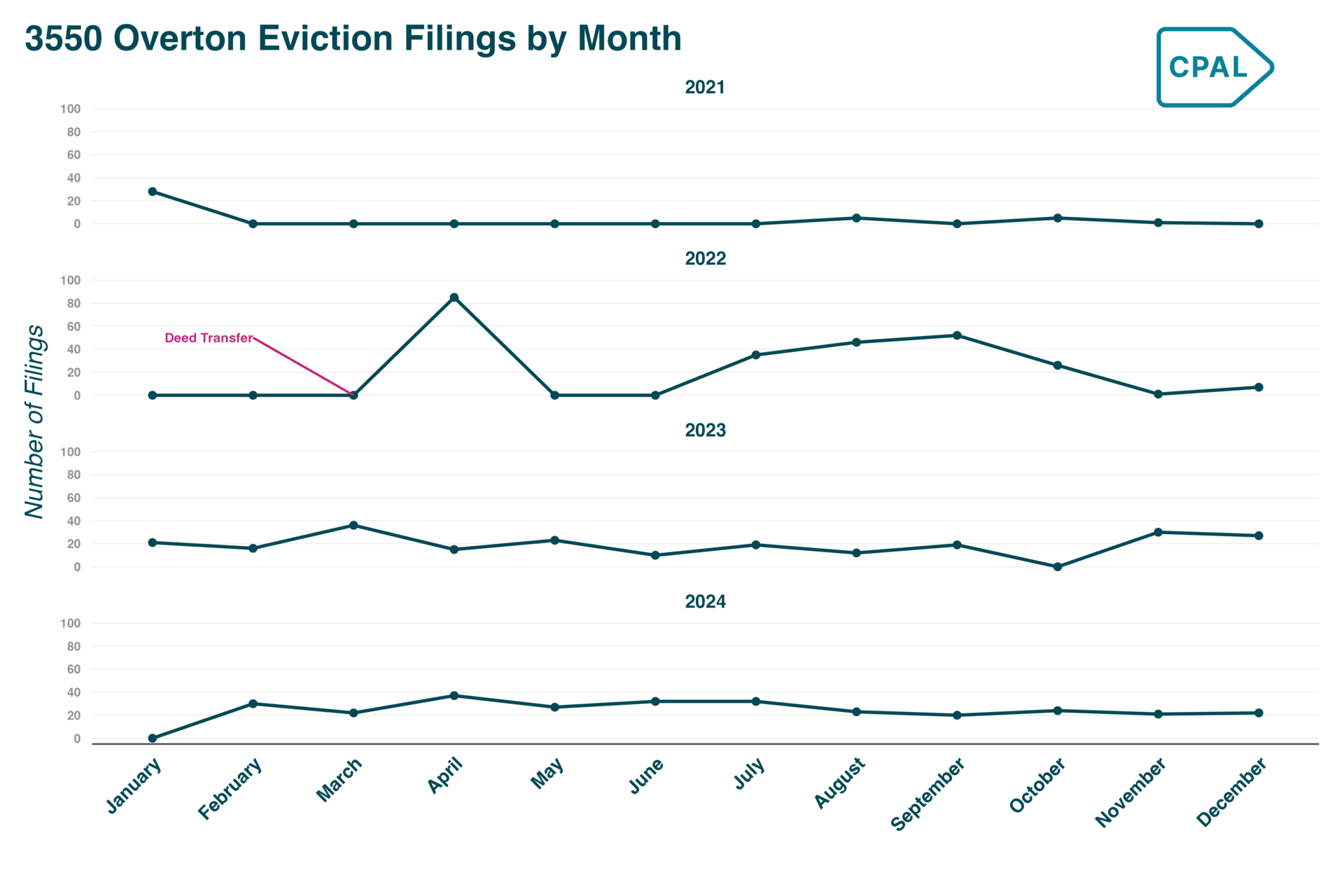

Monthly eviction filings at the Volara apartments since 2021. It had the fourth-highest eviction count of all complexes in the county over the last three years. (Analysis by CPAL)

Grant says conditions might’ve improved at Volara, but it happened as people who had lived there for generations were evicted. Since 2017, the property has been purchased and sold three times, records show, and in the last three years Volara had the fourth-highest eviction count of apartment complexes in the county. More than 200 evictions have been filed here each year. (Including the families of the two boys they encountered walking in the parking lot in the fall of 2024, Grant says.) When people are evicted, they spread out, usually to neighboring apartments or wherever relatives lived. They’d been hurting, Grant says. Maybe some were engaged in crime, maybe they were behind in rent. Maybe both.

“If the people are already in low-income situations, it’s gonna pile up,” he says.

What actually works, he and Perez say, is fostering community. Someone needs to show them how to get tickets off their records. How to do their community service hours. How to get a driver’s license. Perez and Grant have driven people from Volara to North Dallas, then to East Dallas for meetings and appointments. “These people can’t get on the bus and in one day make all these appointments,” Perez says. “Everything that’s needed is somewhere else.”

Johnson, the former Dallas ISD trustee, is now a City Council member who represents the district that includes Volara. He remembers a boxing gym near the complex that he used to frequent as a child. It’s since closed. “My community has been disproportionately disenfranchised, underfunded, ignored, and now we’re fighting to get the resources that we should have had a long time ago,” he says. “If we get these resources, problems like Volara will come all the way down.”

Despite their organization losing its funding, Perez and Grant stay in touch with the people they met at Volara. One summer day, Grant told Perez some tenants needed groceries. “ When you get that call, do you say, ‘Oh, I can’t help?’” Grant says.

“You can’t,” Perez replies.

Volara is one of hundreds of multifamily apartment complexes in Dallas that house low-income people who face similar challenges. The two still volunteer across the city, growing intimately familiar with each property and those who live there. At Volara, they know the hidden alleyways where people sell drugs, the slabs where dilapidated buildings once stood, the field where kids loiter after sunset. But they can also tell you about the state of affairs for tenants at Cherokee Village in Pleasant Grove, the Estelle Village near Paul Quinn College, and the Peoples El Shaddai Village (nicknamed “Butter Beans”) across the street in Oak Cliff.

And every 60 days, the police department updates its list of hot spots, letting the data inform where they increase enforcement. Sometimes, the cycle begins anew.

Kelli Smith is a staff writer for The Lab Report. [email protected].

Read More From The Lab Report:

Oak Cliff’s Steady Heartbeat Toni Johnson is too busy at Roosevelt High School to recognize that she has become one of the most essential pieces in Dallas ISD.

A New Approach for the Most Notorious Trail in Dallas The Cottonwood Creek Trail in North Dallas has long been an unsolvable problem. City Hall’s new partners believe they know what’s been missing.

Why Starbucks is Coming to South Dallas The announcement itself is big news. But so is the story behind the decision to invite the national chain to the Forest Theater.

Randy Bowman’s Radical Philanthropy At a time of great need, the founder of a nonprofit boarding operation believes philanthropic organizations can learn even more from the people they serve.

Has Oak Cliff’s Deck Park Won the Trust of Its Neighbors? Halperin Park will open in the spring over Interstate 35E, near the Dallas Zoo. Residents are watching closely.

We’ll send a new story to your inbox every Wednesday. Have a friend who would appreciate it? We’d love for you to forward this email to them. You can also find all of our work here.

The Lab Report Dallas is a local journalism project published by the Child Poverty Action Lab (CPAL). Its newsroom operates with editorial independence.

© 2025 Child Poverty Action Lab. All rights reserved.